Work in Progress 2022-Ongoing

The Ice Patch Project

Supported by The Trebek Initiative, National Geographic Society and Royal Canadian Geographic Society

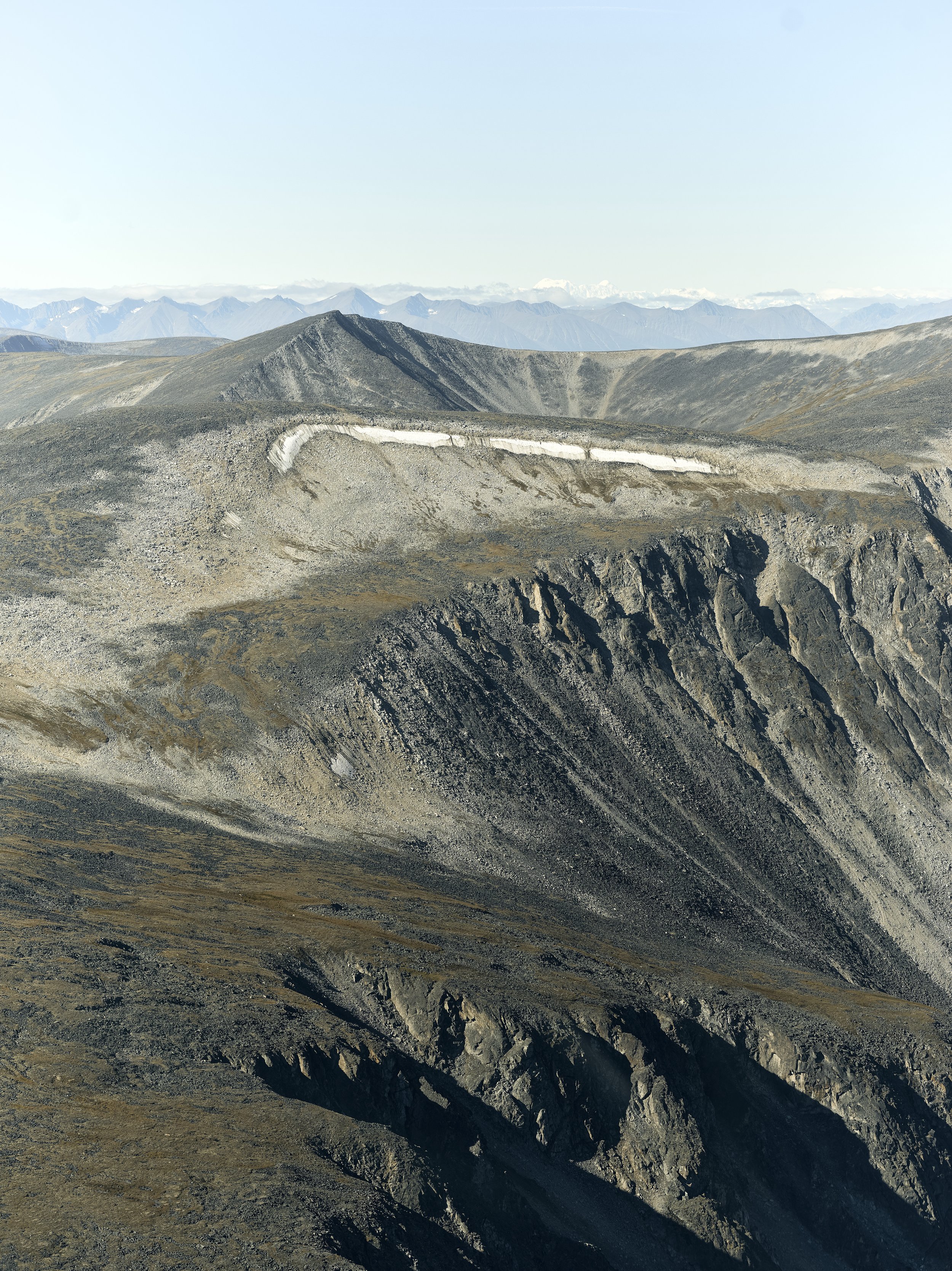

The Gladstone Ice Patch in Champagne and Aishihik Territory. Ice Patches, which are localized areas of ice that remain frozen throughout the year in the Yukon, are an incredible window into the past. Today, because of climate change and rising temperatures in the north, hunting artifacts including arrows, dart shafts, and animal remains that have been carbon dated as far back as 9300 years ago are melting out of the ice.

For thousands of years caribou would come to the alpine ice patches to spend their warm days seeking refuge from the heat and bot flies on the small patches. First Nations, reliant on the caribou and sheep for food and hides knew exactly where to begin their hunt.

The tip of an arrowhead attached to a carved piece of wood with sinew found in the summer of 2023 at the base of the Gladstone Ice Patch. Sinew is a piece of tough fibrous tissue like a tendon or ligament that can be used as a strong string to attach a stone tip to an arrow.

Ice melting over frozen caribou droppings in August 2023. 2023 was the hottest year on record in the Yukon, and the worst wildfire year Canada has ever seen. Climate change puts Ice Patches in danger. Previous studies have shown an ice patch can melt as much as three meters in three weeks.

Eventually these ice patches will completely disappear, and so First Nations, along with the Yukon Government have been collaborating to bring citizens onto the land to search for these artifacts. Together they survey 30-40 of the 330 known ice patches in a year.

Sheep dot the mountainside, and run up the side of the mountain away from the East of East Gladstone ice patch.

Juliette Joe, a highschool student and CA citizen looks over the Gladstone Ice Patch. Shortly after this photo was taken she spotted a piece of an ancient dart shaft.

Jay Reid explores an ice patch in August 2023, 15 years before his father found one of the most impressive artifacts to date. Jay is part of a second generation of CA citizens that have been able to search the Ice Patches for the tools of their ancestors.

An ice patch that has completely melted taken in August 2023. You can see how the grass is slowly beginning to grow over the black caribou dung.

If an artifact is not found in the year it melts out of an ice patch it will begin to deteriorate. If it isn’t found within five years of melting out of the ice the artifacts are at risk of being gone forever. Above is the shaft of a hunting dart broken into multiple pieces. This is a photograph of exactly how it was found.

Ice Patches are not a common phenomenon. It is only the perfect combination of snow fall, seasonal temperatures, and altitude that have allowed 330 to form in the alpine regions of the Yukon. 43 of these patches are identified as archaeological sites and a further 110 are recognized as strictly paleontological sites containing only animal specimens.

A helicopter lands at the base of an ice patch. Most ice patches are so remote they are only accessible by air.

The artifacts found here span an astonishing age range, from a 9000-year-old dart shaft to a 19th-century musket ball, making the Yukon's Ice Patches one of the world's oldest and continuously used hunting grounds.

Champagne and Aishihik Territory.

Glaciers form gradually over time, and when they accumulate a sufficient mass, they flow. Due to their dynamic nature, objects lost within a glacier are subjected to compression, distortion, and a loss of contextual information. Ice patches on the other hand are so small they don’t move. Because of this, the objects lost in them are found thousands of years later in relatively good condition.